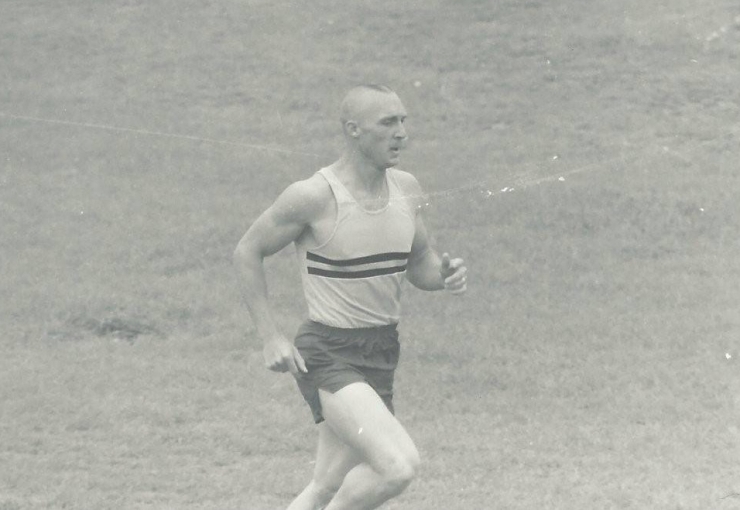

When I was a new runner in New England reading my bi-monthly Runner’s World over and over and over again, I remember black & white photos of a distance runner in the Pacific Northwest who always seemed alone and soaking wet and having a great time. Hair plastered, eyes tight, he was a winner. Not famous. Might’ve even been the same photo. Over and over again. – JDW

When did you start running and why?

When I was in the 7th grade, Alan Adkins said, “Let’s turn out for track and field.” I asked him what that was, and he said “You run and jump and throw things.” That sounded interesting, so we showed up the first day of practice but were told that it was for 8th and 9th graders only. Lake Stevens High in those days included grades 7 through 12. With 7th to 9th grouped together usually in junior high sports – football, basketball, baseball and track.

A year later, I showed up for this strange new sport. I chose the long jump (neé broad jump) because I wouldn’t have to go over a bar or anything and the 660 yard run because nobody else would run that far.

You have to realize I had spent my elementary school years as a sickly child. I was withheld from recess most of the time; I missed 45 of 90 days one semester of second grade. I was the only kid growing up at Lake Stevens who did not learn to swim before he was 12 years old. I learned to swim in a river during Boy Scout camp.

It was probably great for my self-esteem to be the best at something, albeit due only to lack of competition. I did okay in both events. In the ninth grade Buzzie Schilaty was better than I was, but he opted for the 330. His dad (Walt Schilaty) was one of America’s top 100-yard sprinters in the 1930’s. Walt watched me during my races and noted I could beat everyone through the 440, but the rest of the free world seemed to go by after that.

Digression. Walt was a 100 runner who I was told qualified for the Olympics but couldn’t afford to go. The last time I looked he was still at Western Washington University (Bellingham Normal when he was there; Western Washington State College of Education and Western Washington State College when I was there) top ten in the 100. He is in the WWU Hall of Fame. I’m in there as well. When I gave my little speech, the first thing I said was “Thank you for not judging me while I was here.” I lettered one year because of the points I scored in the broad jump and the hop, step and jump ( the names changed after 1996).

First, he showed me how not to “run like a girl.” That was years before Title IX. Girls my age played field hockey and six-girl basketball only against their schoolmates at LSHS. He also talked to me about going out too fast, so I followed his advice, held back and almost fell down with 220 to go because I had so much left. After that I was competitive in both events.

By my junior year I had dropped my mile time to 5:03 which was pretty good for our league. As a senior I ran the 100 yards (10.7), the 440, and broad jumped. I made it to state in the jump that year (1962) and placed 11th, the last year Washington had only one huge state championship. That was also the last year the 440 was run from a straight line across the track with everyone aiming for pole position, and I think the last year for the 220 on the straightaway.

Back to Buzzie. After my ninth grade year, Walt withdrew Buzzie from Lake and rented an apartment so his son could run for Snohomish High, coached by Keith Gilbertson, Sr. At the end of the year, Buzz called and urged me to join the Everett Elks track team which included athletes from all over Snohomish County and was coached by Gilbertson. He convinced me that Gilbie could really improve my performances.

I had no idea how true that was going to be. Right away I could see improvements in my jumping, but this guy, no matter how much I improved, kept subtly sticking me in with the distance runners. He was a soft-spoken man, never raised his voice or threatened in even the slightest way, but when he said to do something, we all knew it should be done.

The team wasn’t a bunch mediocre athletes unlike yours truly; it included the best runners, jumpers and throwers from the county as well as a few world-class athletes (Cliff Cushman, Olympic silver in the hurdles and Helen Thayer, discus thrower from DownUnder. I jumped in such events as the Oregon AAU championship and then sat in the infield and watched America’s best milers (Burleson, Grelle, San Romani, Jr., and others) and realized they weren’t very fast. They were just going 60-second laps. I could do that in tenth grade. I just couldn’t do 1.5 of them. I lacked endurance.

Basically, Gilb kept me in the game past high school.

Of course, I joined the cross-country team at Western Washington State College of Education (imagine that much on the back of a warmup jacket) and can claim only one moment of success of any kind. Our five guys my junior year went to Whitworth University on the opposite side of Washington for the NAIA district championship. Somewhere late in the race I caught our Number 4 runner who was walking and heading toward the cars.

Now, Keith had taught me how to race. I knew to blow by #4 as hard as possible to crush his spirit, but instead, I said, “Jog with me.” He did, and when he saw the finish line, he used his 49-second 440 speed and left me in the dust. Last again, but my name is engraved on Western’s first-ever NAIA title, and I claim the position of being the most valuable member of the team. Jim Freeman may have been among the leaders, but if Phil Walsh is allowed to quit, we don’t win.

Anyhow, I kept running and jumping after college with distance starting to win out. One day at a summer practice Coach Gilbertson said, “Jimmy, you need to get more consistent.” Somehow that clicked with me. I had run whenever I wanted and taken time off whenever I wanted and hadn’t given anything else a thought.

I started to run more often and within a few months put the last zero into my diary. If I can run each of the next however many days, I will have run 50 years without missing a day of running. [February 15, 2020 seems about right.]

My goal of rising to mediocrity, the middle of the pack instead being a straggler, lasted only a short time as consistency put me in a position to win a lot of medals. Thank you, Keith Gilbertson, Sr.

Well, you asked a simple question, but I didn’t find the answer so simple. I had a slow start in the running business. When I was inducted into the WWU Hall of Fame, my first comment was “Thank you for not judging me while I was here.”

Toughest opponent and why?

Well, in some ways, Frank Bozanich was my fiercest opponent. He would hammer from the start, whereas I liked an even pace. I had to hope he wore out before I did. The only times I beat him came when I ran more his style or when someone else ran him into the ground.

We were both at a 50 championship race in Chicago where they held a banquet or something. We were all asked to speak a little I just remember some idiot getting up and saying how great Bozanich was, how I had held the American record, and how there were others in the same range. “I wouldn’t be surprised if someone set a new world record tomorrow.”

This buffoon was dressed in cowboy boots and wearing a cowboy and saying things like that. Where did they dig him up.? Well, to make a short story long, the guy’s name was Barney Klecker. He was unlike any ultra runner I had ever seen.

Before Barney arrived on the ultra scene, we would often talk to each other in the early stages. On out and back courses we would wave, nod, somehow acknowledge each other as kindred spirits.

Klecker had none this. His eyes were set on the concrete pathway the way you see a 10k racer. It was all business. On the bright side, it wasn’t too discouraging. This idiot could never hold that pace. He would die soon. And, indeed he did. His last ten miles were much slower, but, to our surprise, they were faster than even our first ten miles. Barney Klecker set a world record that day. Obviously, he knew something we didn’t. Barney Klecker was the real deal.

I told his wife this story at the reunion of the first U.S. women’s marathon trials in which she competed. And recently cheered for their son as he won an NCAA cross-country regional championship.

Most memorable run and why?

The AAU American championship in 5:12:41. A new U.S. record is memorable. Same as an hour run of 11 miles, 844 yards – done in the midst of hard training – because it was a short race where I did fairly well. These are probably my two best races, but the most memorable may be a 20-mile in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

It was the BC championships. I live about 20 miles from Canada, the distance was right, and they always put on good races. I had never broken two hours for that distance, but I thought that maybe I could run 1:57 if everything worked right. The problem was my monthly visitation with my young son ended up being the day before the race. I couldn’t miss seeing him, so I spent all day Saturday doing son and dad things until around 8 p.m. I returned him to his mom, stopped and bought a bag of cookies and a bag of Snickers candy bars and commenced the 350-mile drive.

I ate all the cookies and all the candy bars. Around 2 a.m. I pulled into the driveway and found half the Snohomish Track club in my house. I got fewer than four hours sleep and woke up sick to my stomach. I wasn’t ill. It’s how one must feel after eating all those peanuts. Good sense told me I used bad sense and the sub-two-hour 20-mile would have to wait. With others depending on me for rides, I still had to drive up to Brockton Oval.

My decision was to run the first five miles and quit. My alimentary canal could hold its contents that long. So I entered the race. At the five-mile mark I had set a new PR (since I was in Canada, that would be a PB). My stomach didn’t feel any worse, so I decided I could run one more lap and quit. I did continue and set a new PR/PB. I actually felt pretty good, so I thought I could last for one more trip around before I stopped.

Result: a third PR/PB of the day. Having run that far and being in the lead, I couldn’t quit. However, now the end was near and my mind took over. I faded as expected, but at the finish I was third in the BC championships and still held on for a sub-two hour time of 1:49:11. That’s not a typo. I ran a full ten minutes under.

What is so memorable is that a freakish set of events took my head out of the race which allowed my body to perform at the level for which I had trained. I tell this story to the athletes we coach when they seem to be getting into their own way. My son Joel tells them about my achievements, so they have no idea that I may have dealt with the same demons that afflict them.

When Joel coached at the college level he would fly me in at the end of cross country, indoor and outdoor seasons which made his teams feel as if they were getting special treatment. It didn’t matter to them they were actually all better than I was and my distances aren’t even remotely the same as theirs.

Biggest disappointment and why?

This one is easy. In December of 1977, I flew to Santa Monica with the intention of winning the AAU national 50-mile track championship. Unfortunately, Ken Moffitt arrived with the same plans, and his were apparently better than mine. I had no trouble running in second place, but at around 40 miles I slipped back to third. Was tired and being beaten and just stepped off the track. My brother had driven my Porsche 914 to LA, so I grabbed my stuff, we headed north hoping to get to Eugene to watch friends in the OTC marathon.

It wasn’t until we passed Sacramento that I realized I could have jogged in and still been third in the national championships. I have forever regretted this. When I was still the American record holder, I wrote a book on running. Recently, my son Joel got me to revive the effort and update it a bit. In the racing section, I added a few paragraphs under the sub title: There Must Be a Plan B which isn’t a copout, but a “what if” option.

Jacqueline Hansen told me she stopped as well. She knew she could no longer set the 50-mile record, but not finishing would negate the 11 world intermediate records she had already recorded. She hopped back into the race and finished in 7:14, not what she had wanted but still not a bad time.

What would you do differently if you could do it again? Why?

I just found the missing answers to your questions. Since I found them, I thought of two more memorable moments:

In February of 1972 when I ran 2:25:35 at the Trail’s End Marathon in Seaside, Oregon, I passed Gerry Lindgren with 2.5 miles to go. I said, “Hang tough” and got a “Hi” in return. Now, beating Gerry was cool, but I’m savvy enough to know that beating Gerry Lindgren didn’t make me as good as he was. What was so memorable to me was he spied me at the post-race chili feed and came over and said, “How could you look so tough when you passed me.” To have him remember me and to give me that compliment was an overwhelming gesture.

The other memorable moment was initiated following my October 25, 1977, American record 50 mile run. Defending AAU 50 champ Max White was a good sport. He gave me a high five as he crossed the line for the out and back final two miles, and we talked about various things after he finished.

One thing he said stuck out: “It’s too bad you can’t be in the Olympic Trials.” I asked him why, and he responded with “Because you have to qualify by the end of the year, and you won’t be able to run a marathon for at least six months.”

He said that as a statement of fact, but I took it as a challenge. I thought of that every day until the Portland Marathon 34 days later where I ran 2:22:32 to qualify for the 1976 trials.

Favorite philosopher? Quote?

Don Kardong: “Without ice cream there would be darkness and chaos.”

Satchel Paige: “How old would you be if you didn’t know how old you were?”

Special song of the era?

“59th Street Bridge Song” by Simon & Grafunkel.

Favorite comedian?

At the time it was the Brothers Smothers and Bill Cosby.

What was your ‘best stretch of running’?

From 1974 through 1984 I ran 67 races from 26.2 miles to 100 kilometers:

1974 placed 5th in AAU 50k in3:10:29; injured due to taking advice from friend.

1975 1st in AAU 50 mile in American record 5:12:40.1; 3rd in marathon 34 days later 2:22:32 to qualify for ’76 trials.

1976 2nd in AAU 50k 3:03:39; 33rd in trials.

1978 Oregon AAU first in 5:47:42

1979 2nd in RRCA national 100k 7:44:10; 2nd at Yakima 100k in 7:44:10; 3rd in AAU 50 mile 5:38:51’

1980 3rd in RRCA 100k 7:51:51; 1st in Yakima 100k 7:07:49; 5th in Chicago 50 in 5:32:48.

1982 1st in 60k 3:49:14

My 60 k and track 50 in Santa Monica were both 4th best U.S. all-time (at that time).

My two best 100ks were second fastest U.S. ever. Between the first and the second someone passed me. I had a bit of trouble in Eastern America races since I taught until 3 p.m. before traveling over 100 miles by car to get to SeaTac to fly across the country. The Florida 100ks started a few hours after I landed.

And so why do you think you hit that level at that time?

From 1974 through 1984 I ran over 57,500 miles. I averaged 100 miles a week for 11.5 years. I set personal records for shorter runs, usually during my second or third run of the day. Was very fit.

What was your edge?

My edge was that I really didn’t feel that I was that good, so in my mind I was always the underdog in the race. That actually takes off a lot of the pressure. It’s odd. Since I felt that way about myself, I really didn’t think some of the people I always beat were that good. In my old age I look back and realize some of them would be winning races today with the times they ran back in the day.

I didn’t look down on anybody, but these people were always behind me. I just realized lately that in the long things I didn’t even know who else was there beside the few I really had to tangle with. It’s hard to believe that I had such a narrow focus. It wasn’t until I read Kenny Moore’s Bowerman and the Men of Oregon that I understood the Olympic trials course was two laps and that it was the same course as the ’71 nationals and the ’72 and ’76 trials. I ran in all three.

I’ll be honest. Never had much interest in going past twenty-six-miles-and-three-hundred-and-eighty-five yards. The marathon was long enough for me. Why become an ultramarathoner?

I was finishing marathons without getting very tired, so trying something longer just seemed like the thing to do.

Getting injured before the 1974 50k may have been to my advantage since I just kept moving close to training pace and never got truly involved in the race itself. The result – for whatever the reason – gave me the idea that I could run 50 miles. I was surprised recently when I transcribed my 1975 diary; I wrote two paragraphs at the start about my plans for the year. They included running over 11 miles in the Hour Run and running in the National 50-mile and even trying to win it.

You know how the 50M turned out, but the 11 miles and 844 yards in the hour showed that I was improving. I had run over 5,400 miles in 1974 and was about to run much more than that in 1975.

A little less than five months after the 50-mile, I placed second in the heat of Sacramento in 3:03:39 for 50K. There were no aid stations that I recall. I was really disappointed in my effort. There was no way, however, I could match the awesome race that Chuck Smead ran that day. [ Smead’s obscenely fast 2:50:46 was an asterisked American record for years due to different measurement standards. Chuck is another OGOR, if I can find him.]

A week before the 1974 AAU National 50k Championship I was hanging out with Guy Renfro at a Snohomish Track Club get together. Guy had run at the University of Oregon. He seemed to have an in-depth knowledge of running science. His daughter Sarna later won several Washington state titles in cross country and track.

Anyhow, we were talking about the upcoming 50k which I was going to run. He asked about my training, which had been two a day runs totaling a bit over 100 miles a week. He asked about long hard runs, and I responded that I hadn’t run any. He said I wouldn’t run well if I didn’t do any, so five days before the big race, I ran 14.1 miles in the morning and 10.3 later that day which ended with a painful leg injury. I wasn’t sure until race day that I would actually enter the race.

I have this image of you soaking wet. What’s your thinking about running/training in the rain?

That’s a tough question. I enjoy when it doesn’t rain, and in a normal year it does rain often, not a lot, but often. This year was one of the six dryest years since I was born.

I remember standing with a group of Ferndale High School runners at the glass door as we peered out into the rain. We would just stand there waiting. eventually someone (maybe I did it; maybe one of the kids) would open the door, and our run would begin. That would happen often. The hard part was over. The worst part after opening the door was that there was always some kid who wanted to hit every pool of water available for splashing everyone.

Running in the rain isn’t that bad; going out into it is.

In Marysville where I now live, about 75 miles below British Columbia, the wind does not blow as hard or as often as it did in Ferndale which is fifteen miles below BC. It’s the wind with rain that can be difficult for running, so things are better in this area.

The simple answer to your question is that running in the rain is just a nuisance; opening the door to get out there is the hard part.

I was fortunate enough to have it rain the morning of my 50-mile record run. Of course, that’s not what I felt as I drove in the rain to Seattle that day. I had never had anything to drink or eat during a race, so the 50-mile would have been no exception. When I complained about a slight hamstring cramp after 33 miles, one of my running friends suggested that the cramp may have occurred because I was not drinking. At 39 miles I took a swig of some drink and at 42, I did the same. In total that was four or five ounces. The nastier weather probably kept me from sweating a great deal.

Don Kardong said something once about training in Seattle and referenced the image of a spider getting washed down the sink.

Kardong has lived too long on the east side and probably has just a blurred vision of his younger days. I cannot relate to the spider analogy. Once you’re out there and running, all is good.

I must admit that before we moved to Spokane for that brief few years that I had no idea how hard it was to train in Whatcom County, Washington. In Spokane the thermometer dropped much lower than on the west side. However, running in a temperature as low as negative 11 never bothered me. On west side, going to a track meet on a warm day in April becomes unbearable as soon as the sun drops below the horizon. The same with the higher temperatures. At 95 in Spokane, things are good. At 85 in Bellingham, it is miserable.

I’ve got a ton of photos, but I think I’ve probably figured out the photo you mentioned. I believe that it appeared in the February 1976 Runner’s World. I’m pretty sure they never returned the negative. It was during the Portland Marathon which was held on Sauvies Island 34 days after my 50-mile run. That may be why you thought I looked determined or however you described it. I do think the 50-mile did affect me a bit, but I did get the job done.

In the early Eighties, when I was a Master of the Universe at Nike, HR held an intramural half-marathon on Sauvies Island. I paced a young woman to a time which qualified her for a trip-for-two to Hawaii. She ended up taking her mom.

Years ago now, son Joel Pearson penned this report.

Jim Pearson’s Sample Training

Jim was basically a self-coached athlete who followed somewhat the teachings of New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard and the advice and encouragement of his summer coach, Keith Gilbertson, sr.

In retrospect, he has been heard to say that his training mirrored that of the great Clarence DeMar, the seven-time Boston marathon winner: very high mileage with short local road races tossed in. Since he never thought of himself as a good runner, this low key attitude about intensity seems quite logical. The higher than normal mileage rose out of a self-imposed challenge to see what his body could handle.

As a result, he had an 11 1/2 year stretch where he AVERAGED over 100 miles per week. His longest streak of consecutive 100 miles or better weeks hit exactly a year and a half: 78 weeks. Pearson ran no exceptionally high weekly mileage–a best of 185 miles–but recorded some fairly high months–729 and 719 (back to back). His two best years were 6,174 miles in 1975 and 6,028 miles in 1978.

This type of mileage led to a fairly easy AAU National 50 mile title in 5:12:41 for a new American record. The endurance was further emphasized by his running a 2:22:32 marathon just 35 days later. The key to his progress was consistency which led to a streak of over 49 years without missing a day of running.

Pearson admits that had he had a coach who controlled his practices, he would have run more short and intense workouts. “With the training program I used,” Pearson explained, “I was able to surpass 2:45 in the marathon which was my lifetime goal. In fact, when I started running the ultras, I could run the first 26.2 faster than that. That was the case in the record run, and then I ran the last 25 miles at a faster pace.”

When he ran the marathon just five weeks later, he slowed only 25 seconds on the course which consisted of two identical laps. Most of his successful races were run with negative splits.

“My greatest mistake was not in my training, but in my failure to rest adequately. I tapered well for the record 50 mile (see below), but later would run a marathon in the 2:40 range the week before an ultra. In retrospect, I can see that decision as being a mistake.”

My 7:07: 49 100K win in Yakima, WA. Second best by an American at that time.

Sample of training: (21 weeks)

The 16 weeks prior to Pearson’s 50 mile American record: (# is miles that week)

1) 158 5) 161 9) 166 13) 119

2) 165 6) 159 10) 130 14) 123

3) 175 7) 158 11) 125 15) 109

4) 166 8) 161 12) 130 16) 111

Week 17=102 miles and a 5:12:41 American record for the 1975 U.S. 50M Champs!

Note: Tapering for the race began seven weeks before the championship race.

18) 109

19) 142

20) 106

21) 113

Week 22 = 104 miles and a third place finish – Portland marathon 2:22:32.

Note: After a rest week (109 miles), a longer week was run before tapering resumed.

If your idea of a rest week is 109 miles, you might just be an OGOR.

The timeline of me being a new runner doesn’t align with Jim’s appearance in RW. Memory conflict, not fake news.